Friday, February 25, 2011

From the Vogue Archives:

Photographer Henry Clarke captures models Marisa Berenson and Cynthia Korman in Isfahan, Iran. Vogue, December 1969

Thursday, February 10, 2011

A Note from The Polyglot

Thursday, February 3, 2011

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

From the Vogue Archives: Orient Excess

One of the more recent examples of “Orientalism” (by way of Edward Saïd), at work in the fashion world appeared in the pages of British Vogue. For its June 2008 issue, the publication asked Rana Kabbani, the noted Syrian cultural historian, to write a two page essay addressing the myths surrounding the Oriental harem within the Western imagination.

One of the more recent examples of “Orientalism” (by way of Edward Saïd), at work in the fashion world appeared in the pages of British Vogue. For its June 2008 issue, the publication asked Rana Kabbani, the noted Syrian cultural historian, to write a two page essay addressing the myths surrounding the Oriental harem within the Western imagination.Born in Damascus, Kabbani was educated at the American University of Beirut and Jesus College, Cambridge. After working as an art critic in Paris and a publisher's editor in London, she became a full-time writer in 1986. One her most important works was “Europe's Myths of the Orient: Devise and Rule” (1986), which examined Western perceptions of Islamic culture, paying particular attention to the creation of erotic stereotypes within European literature and painting. Her seminal book was later republished in 1994 as “Imperial Fictions: Europe's Myths of the Orient.”

In her article for Vogue, Kabani dispels many of the misconceptions surrounding the age old institution of sequestering women, by poignantly recalling her own grandmother’s life spent in a Damascus harem during the twilight years of the Ottoman Empire. Kabani’s words are surprisingly frank, direct and insightful, offering the reader an unvarnished viewpoint, far removed from the romanticized vision of 19th century Victorian painters. Ultimately her piece is a critique of cultural misrepresentations encouraged by such artists; noting that the women in such paintings were often portrayed as passive. When in reality, the harem (at the time) served as a venue for women to converse, work, entertain, and learn from each other in an environment, “relieved of the intrusive presence of their men.”

In her article for Vogue, Kabani dispels many of the misconceptions surrounding the age old institution of sequestering women, by poignantly recalling her own grandmother’s life spent in a Damascus harem during the twilight years of the Ottoman Empire. Kabani’s words are surprisingly frank, direct and insightful, offering the reader an unvarnished viewpoint, far removed from the romanticized vision of 19th century Victorian painters. Ultimately her piece is a critique of cultural misrepresentations encouraged by such artists; noting that the women in such paintings were often portrayed as passive. When in reality, the harem (at the time) served as a venue for women to converse, work, entertain, and learn from each other in an environment, “relieved of the intrusive presence of their men.”The “noisy, active, ferocious, brave, hard-working, opinionated and fun,” behavior that Kabbani witnessed in the harem women of her grandmother's generation is meant to humanize and give a face to the subjects of Orientalist paintings. She also makes the point that harem life was far less “exotic,” than what was portrayed in Western literature.

To look at the Oriental-inspired fashion spread on the preceding 6 pages provides an interesting social and historical counterpoint. Where Kabani’s essay attempts to shatter the myth, the photographer Janvier Vallhonrat and fashion editor Lucinda Chambers seem to perpetuate it. In a series of atmospheric images, the model Élise Crombez is captured lounging amongst embroidered pillows and a sea of Kilims, in scenes far removed from the thought-provoking world painted by Kabani. Despite this, what’s interesting about Vallhonrat’s images (when compared to that of his 19th century predecessors), is the hint of defiance in his subject’s eyes, and the suggestion of some form of struggle (through the use of hair and makeup).

To look at the Oriental-inspired fashion spread on the preceding 6 pages provides an interesting social and historical counterpoint. Where Kabani’s essay attempts to shatter the myth, the photographer Janvier Vallhonrat and fashion editor Lucinda Chambers seem to perpetuate it. In a series of atmospheric images, the model Élise Crombez is captured lounging amongst embroidered pillows and a sea of Kilims, in scenes far removed from the thought-provoking world painted by Kabani. Despite this, what’s interesting about Vallhonrat’s images (when compared to that of his 19th century predecessors), is the hint of defiance in his subject’s eyes, and the suggestion of some form of struggle (through the use of hair and makeup).Yet for all the analysis, what Vogue does best are beautiful images meant to inspire and take its readers on a journey (if only for a few minutes)…it’s just more interesting when a bit of social commentary is thrown into the mix.

Orientalism Exposed

The Polyglot explores the Orient’s influence on generations of designers in the West, and asks the question, “when is ethnic too ethnic?”

Looks from Paul Smiths’ Orientalist inspired Spring 2009 collection.

Looks from Paul Smiths’ Orientalist inspired Spring 2009 collection.

One wonders what Edward Saïd, (the late Palestinian literary theorist, cultural critic, and political activist) would have made of the round of spring collections that took place in New York back in 2008. As one flitted through the tents at Bryant Park, it was difficult to ignore a certain whiff of the Middle East permeating through many of the shows. All the more ironic considering that the New York Spring collections traditionally fall around the same time as the anniversary of the September 11th attacks.

In Saïd’s seminal work, Orientalism, he points to a long tradition in the West of creating a romanticized vision of the Orient. He argued that Western depictions and writings on the Orient are often colored by a history of European colonial rule and political domination over the region; and that this history ultimately distorts the art and writings of even the most knowledgeable, well-meaning and sympathetic of Western “Orientalists.”

Looks from Paul Smiths’ Orientalist inspired Spring 2009 collection.

Looks from Paul Smiths’ Orientalist inspired Spring 2009 collection.

Which leads one to wonder if Western designers are also prone to perpetuating a somewhat contradictory image of an exotic Orient? This apparent contradiction seemed to be on the minds of several designers that particular season. In fashion nothing happens haphazardly as it is often a reflection of social, cultural and political currents occurring at any given moment in time. This was no more apparent than across the Atlantic at London Fashion Week that same year, where the designer Paul Smith presented his own take on Oriental chic with a collection that included variations on the “Turkish waistcoat” and softly flowing harem pants. Backstage at the designer’s spring 2009 show, both makeup artist Petros Petrohilos and hair stylist Peter Gray said that Smith’s directive was to create a “hammam chic-fresh out of the spa” look.

Smith himself, was candid about the fact that his show was very much an allusion to an “imaginary East.” No surprise considering that for this collection the designer immersed himself in the "The Lure of the East," the Orientalist show at the Tate museum in London that summer, which explored the Orient through the eyes of Victorian painters. In a sense, that particular exhibit could be seen as a visual counterpart to Edward Saïd’s thesis. What Paul Smith proposed as a designer was to continue that conversation in the context of a fashion show.

Looks from Miguel Adrover's Fall 2001 collection, inspired by the traditional Egyptian dress of the Nile Delta.

Looks from Miguel Adrover's Fall 2001 collection, inspired by the traditional Egyptian dress of the Nile Delta.

Back in New York, time has an interesting way of healing wounds (or at least changing perceptions), when one considers that it was only a few season’s ago that the designer Miguel Adrover was unanimously panned by critics for presenting an “Egyptian” inspired collection shortly after September 11th. Although his Fall 2001 collection, called “Meet East,” was a breakthrough from a design standpoint, it nevertheless was judged by many as “insensitive.” The incident not only resulted in plummeting sales for Adrover (and his company’s eventual closing); but also became a subtle message to designers (at least in America), that they may want to keep the Middle East off their inspiration boards for the time being.

Looks from Paul Smiths’ Orientalist inspired Spring 2009 collection.

Looks from Paul Smiths’ Orientalist inspired Spring 2009 collection.One wonders what Edward Saïd, (the late Palestinian literary theorist, cultural critic, and political activist) would have made of the round of spring collections that took place in New York back in 2008. As one flitted through the tents at Bryant Park, it was difficult to ignore a certain whiff of the Middle East permeating through many of the shows. All the more ironic considering that the New York Spring collections traditionally fall around the same time as the anniversary of the September 11th attacks.

In Saïd’s seminal work, Orientalism, he points to a long tradition in the West of creating a romanticized vision of the Orient. He argued that Western depictions and writings on the Orient are often colored by a history of European colonial rule and political domination over the region; and that this history ultimately distorts the art and writings of even the most knowledgeable, well-meaning and sympathetic of Western “Orientalists.”

Looks from Paul Smiths’ Orientalist inspired Spring 2009 collection.

Looks from Paul Smiths’ Orientalist inspired Spring 2009 collection.Which leads one to wonder if Western designers are also prone to perpetuating a somewhat contradictory image of an exotic Orient? This apparent contradiction seemed to be on the minds of several designers that particular season. In fashion nothing happens haphazardly as it is often a reflection of social, cultural and political currents occurring at any given moment in time. This was no more apparent than across the Atlantic at London Fashion Week that same year, where the designer Paul Smith presented his own take on Oriental chic with a collection that included variations on the “Turkish waistcoat” and softly flowing harem pants. Backstage at the designer’s spring 2009 show, both makeup artist Petros Petrohilos and hair stylist Peter Gray said that Smith’s directive was to create a “hammam chic-fresh out of the spa” look.

Smith himself, was candid about the fact that his show was very much an allusion to an “imaginary East.” No surprise considering that for this collection the designer immersed himself in the "The Lure of the East," the Orientalist show at the Tate museum in London that summer, which explored the Orient through the eyes of Victorian painters. In a sense, that particular exhibit could be seen as a visual counterpart to Edward Saïd’s thesis. What Paul Smith proposed as a designer was to continue that conversation in the context of a fashion show.

Looks from Miguel Adrover's Fall 2001 collection, inspired by the traditional Egyptian dress of the Nile Delta.

Looks from Miguel Adrover's Fall 2001 collection, inspired by the traditional Egyptian dress of the Nile Delta.Back in New York, time has an interesting way of healing wounds (or at least changing perceptions), when one considers that it was only a few season’s ago that the designer Miguel Adrover was unanimously panned by critics for presenting an “Egyptian” inspired collection shortly after September 11th. Although his Fall 2001 collection, called “Meet East,” was a breakthrough from a design standpoint, it nevertheless was judged by many as “insensitive.” The incident not only resulted in plummeting sales for Adrover (and his company’s eventual closing); but also became a subtle message to designers (at least in America), that they may want to keep the Middle East off their inspiration boards for the time being.

Fast forward to September 2008, and the New York Spring collections not only marked the return of Adrover onto the fashion scene; but also the appearance of a strong Middle Eastern influence on the catwalks of both established and upcoming designers. It could be seen in the Moorish arches flanking the runways at Phillip Lim and Ralph Lauren, in prints and beading alluding to arabesque tiles at Malo, and in the lusciously draped gowns that captured the ease of a djallaba at Donna Karan’s show.

Furthermore, this trend has not gone unnoticed amongst the key players in the business who ultimately influence what we will be wearing next season. Most notable amongst this group is HRH Princess Deena Aljuhani Abdulaziz. At a time when fashion has become an increasingly global business, Mrs. Abdulaziz is one of the few Middle Eastern voices to be heard on fashion’s front lines. Early on she became instrumental in introducing women in Saudi Arabia (and the region) to a new generation of American designers such as Behnaz Sarafpour, Peter Som and Proenza Schouler through her influential concept store D’NA, in Riyadh.

“An Armenian Lady in Cairo, 1855,” by John Frederick Lewis was shown at "The Lure of the East," the Orientalist show at the Tate museum in London. The exhibit was the inspiration for Paul Smith’s Spring 2009 collection; A turbaned model at Chanel haute couture 1989, a look that can be traced back to 19th century Orientalist paintings.

“An Armenian Lady in Cairo, 1855,” by John Frederick Lewis was shown at "The Lure of the East," the Orientalist show at the Tate museum in London. The exhibit was the inspiration for Paul Smith’s Spring 2009 collection; A turbaned model at Chanel haute couture 1989, a look that can be traced back to 19th century Orientalist paintings.

John Frederick Lewis’ “Lilium Auratum,” 1871. A look from Jean Paul Gaultier’s Spring 1998 haute couture collection.

John Frederick Lewis’ “Lilium Auratum,” 1871. A look from Jean Paul Gaultier’s Spring 1998 haute couture collection.

Some of the most interesting interpretations of Oriental costume have come from designers known for a minimalist approach to dress. In this case, Jill Sander and Alberta Ferretti whittle down the caftan to its purist essence, Spring 1994.

Some of the most interesting interpretations of Oriental costume have come from designers known for a minimalist approach to dress. In this case, Jill Sander and Alberta Ferretti whittle down the caftan to its purist essence, Spring 1994.

Yves Saint Laurent would also be inspired by the costumes of the Ballet Russe when he created a collection under the same name. Frequently referencing North Africa (and Marrakech in particular where he had a home), his Spring 1991 collection included colorful harem pants and fez’s inspired by Léon Bakst’s costumes; For Spring 1992 he designed a Moroccan inspired ensemble. Saint Laurent also created Oriental inspired designs for his close friends; In 1977 he designed two wedding outfits for his muse Lou Lou de la Falaise; Bianca Jagger in an oriental inspired outfit at New York’s El Morocco, 1975.

Yves Saint Laurent would also be inspired by the costumes of the Ballet Russe when he created a collection under the same name. Frequently referencing North Africa (and Marrakech in particular where he had a home), his Spring 1991 collection included colorful harem pants and fez’s inspired by Léon Bakst’s costumes; For Spring 1992 he designed a Moroccan inspired ensemble. Saint Laurent also created Oriental inspired designs for his close friends; In 1977 he designed two wedding outfits for his muse Lou Lou de la Falaise; Bianca Jagger in an oriental inspired outfit at New York’s El Morocco, 1975.

For Fall 1994 London-based Turkish designer Rifat Ozbek showed one of his most influential collections in Paris (his first year showing there after presenting in Milan for several seasons). That year Ozbek was inspired by his Turkish roots and referenced Ottoman costumes. But take all those pieces apart and you had thoroughly modern clothes that were beautifully tailored, which was a hallmark of Ozbek.

For Fall 1994 London-based Turkish designer Rifat Ozbek showed one of his most influential collections in Paris (his first year showing there after presenting in Milan for several seasons). That year Ozbek was inspired by his Turkish roots and referenced Ottoman costumes. But take all those pieces apart and you had thoroughly modern clothes that were beautifully tailored, which was a hallmark of Ozbek.

For the show he commissioned Phillip Tracey to design towering Fez’s based on those worn by twirling dervishes. Some came with ostrich feathers perched at their peaks, while others had floor skimming veils edged in silver coins. For the show, the models feet were painted gold and they walked on a runway covered in oriental carpets and rose petals.

The two outfits, worn by models Naomi Campbell and Yasmin Ghauri, demonstrate Ozbek’s talent at reinterpreting ethnic influences. In this case he took the traditional Ottoman military frock coat and reworked it into satin bustiers trimmed in grey fur, which were worn with ball skirts, mimicing the effect of harem pants when the models walked down the runway.

© THE POLYGLOT (all rights reserved) CHICAGO-PARIS

Furthermore, this trend has not gone unnoticed amongst the key players in the business who ultimately influence what we will be wearing next season. Most notable amongst this group is HRH Princess Deena Aljuhani Abdulaziz. At a time when fashion has become an increasingly global business, Mrs. Abdulaziz is one of the few Middle Eastern voices to be heard on fashion’s front lines. Early on she became instrumental in introducing women in Saudi Arabia (and the region) to a new generation of American designers such as Behnaz Sarafpour, Peter Som and Proenza Schouler through her influential concept store D’NA, in Riyadh.

“An Armenian Lady in Cairo, 1855,” by John Frederick Lewis was shown at "The Lure of the East," the Orientalist show at the Tate museum in London. The exhibit was the inspiration for Paul Smith’s Spring 2009 collection; A turbaned model at Chanel haute couture 1989, a look that can be traced back to 19th century Orientalist paintings.

“An Armenian Lady in Cairo, 1855,” by John Frederick Lewis was shown at "The Lure of the East," the Orientalist show at the Tate museum in London. The exhibit was the inspiration for Paul Smith’s Spring 2009 collection; A turbaned model at Chanel haute couture 1989, a look that can be traced back to 19th century Orientalist paintings.

Over the years Abdulaziz has developed a sixth sense for deciphering trends and dissecting the key pieces from collections. When asked about her impressions of the recent New York shows, the influential buyer and fashion icon went straight to the point: “Ralph Lauren and Peter Som each presented their own unique perspective on the whole Lawrence of Arabia look; the references where there on the surface and unavoidable. But beyond the styling, one had to dig deeper to see those influences coming through in other collections as well. Behnaz Sarafpour showed a sleek tunic of cream and gold jacquard, covered in a pattern that reminded me of historic textiles worn by members of the Ottoman court.”

Then there is the harem pant, which according to Mrs. Abdulaziz would be “the strongest trend for both spring and summer.” To be sure, this isn’t the first time “the pant in question” has made an appearance on international catwalks; as everyone from Saint Laurent to Sonia Rykiel have offered up their interpretations at one point or another. But this time around designers offered variations that were less “costumie.” By deflating the air out of the traditional looking harem pant, they produced slimmer versions in a variety of lengths and fabrics that women may actually consider wearing in public.

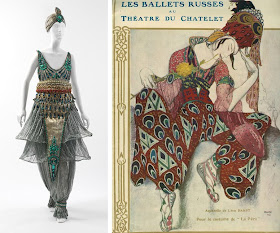

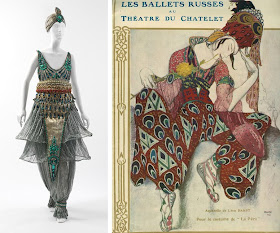

The French couturier Paul Poiret frequently found inspiration in the Orient, creating this “Harem” evening ensemble in 1910. The Ballets Russes, under the direction of Sergei Diaghilev, performed in Paris from 1909 to 1929. During that time it was considered one of the most influential theatre companies, sparking a vogue for all things Oriental when Léon Bakst created the costumes for Scheherazade. Paul Poiret was extremely influenced by Bakst's costume designs for the production, which included bold hues, heavy embroidery and harem pants.

The French couturier Paul Poiret frequently found inspiration in the Orient, creating this “Harem” evening ensemble in 1910. The Ballets Russes, under the direction of Sergei Diaghilev, performed in Paris from 1909 to 1929. During that time it was considered one of the most influential theatre companies, sparking a vogue for all things Oriental when Léon Bakst created the costumes for Scheherazade. Paul Poiret was extremely influenced by Bakst's costume designs for the production, which included bold hues, heavy embroidery and harem pants.

Reinterpreting cultural or ethnic influences in fashion is a fine art; too heavy on the beading and embroidery and you may end up looking like you’ve stepped off the pages of National Geographic. This is especially true for Middle Eastern buyers and editors attending the collections, who aren’t necessarily looking for literal interpretations of Arab costume; a point that is very much on Abdulaziz’s mind as she decides on how to approach the harem pant with her specific clientele in mind. “Some designers did it better than others, and what works for the Arab woman is a modern -not too literal- take on it,” added Abdulaziz.

It’s not often the case that New York designers chose to collectively zero-in on one particular item of clothing. Jill Stuart showed a relaxed pair of harem pants in grey washed cotton worn with a slouchy cardigan and high heels for a thoroughly modern look. Alberta Ferretti and Diane von Fürstenberg showed knee grazing numbers paired with blazers. The young design team of Proenza Schouler integrated their’s into a jump suit recalling the decadent era of Studio 54. While Ralph Lauren’s version came in everything from Khaki to bronze-beaded tulle, which billowed as the models walked down the runway.

Then there is the harem pant, which according to Mrs. Abdulaziz would be “the strongest trend for both spring and summer.” To be sure, this isn’t the first time “the pant in question” has made an appearance on international catwalks; as everyone from Saint Laurent to Sonia Rykiel have offered up their interpretations at one point or another. But this time around designers offered variations that were less “costumie.” By deflating the air out of the traditional looking harem pant, they produced slimmer versions in a variety of lengths and fabrics that women may actually consider wearing in public.

The French couturier Paul Poiret frequently found inspiration in the Orient, creating this “Harem” evening ensemble in 1910. The Ballets Russes, under the direction of Sergei Diaghilev, performed in Paris from 1909 to 1929. During that time it was considered one of the most influential theatre companies, sparking a vogue for all things Oriental when Léon Bakst created the costumes for Scheherazade. Paul Poiret was extremely influenced by Bakst's costume designs for the production, which included bold hues, heavy embroidery and harem pants.

The French couturier Paul Poiret frequently found inspiration in the Orient, creating this “Harem” evening ensemble in 1910. The Ballets Russes, under the direction of Sergei Diaghilev, performed in Paris from 1909 to 1929. During that time it was considered one of the most influential theatre companies, sparking a vogue for all things Oriental when Léon Bakst created the costumes for Scheherazade. Paul Poiret was extremely influenced by Bakst's costume designs for the production, which included bold hues, heavy embroidery and harem pants.Reinterpreting cultural or ethnic influences in fashion is a fine art; too heavy on the beading and embroidery and you may end up looking like you’ve stepped off the pages of National Geographic. This is especially true for Middle Eastern buyers and editors attending the collections, who aren’t necessarily looking for literal interpretations of Arab costume; a point that is very much on Abdulaziz’s mind as she decides on how to approach the harem pant with her specific clientele in mind. “Some designers did it better than others, and what works for the Arab woman is a modern -not too literal- take on it,” added Abdulaziz.

It’s not often the case that New York designers chose to collectively zero-in on one particular item of clothing. Jill Stuart showed a relaxed pair of harem pants in grey washed cotton worn with a slouchy cardigan and high heels for a thoroughly modern look. Alberta Ferretti and Diane von Fürstenberg showed knee grazing numbers paired with blazers. The young design team of Proenza Schouler integrated their’s into a jump suit recalling the decadent era of Studio 54. While Ralph Lauren’s version came in everything from Khaki to bronze-beaded tulle, which billowed as the models walked down the runway.

But amongst fashion insiders, the show that caused the most buzz was Marc Jacobs’s sophisticated collection, which Abdulaziz described as “divine!” Although Jacobs is known for combining a myriad of influences into his designs, one of the most apparent sources of inspiration (a trend also seen in other shows) was Yves Saint Laurent and his ground breaking Ballet Russe collection from the 1970’s.

Algerian born Saint Laurent had a long history of being inspired by the Orient, and in Jacob’s hands those influences have been updated and twisted to resonate with a woman of today. That meant a longer, leaner silhouette, the layering of rich fabrics such as silks and brocades, and the return of accessories as an important final touch to completing outfits. “It was done with such attention to detail, and I loved how Tim Blanks (the fashion critic at style.com) described it as Lana Turner going on a trip to Bali,” said Abdulaziz when speaking of a collection that also captured the spirit (and color sense) of Saint Laurent’s legendary muse and collaborator, designer Lou Lou de la Falaise. A not so surprising choice since de la Falaise wore a turban and harem pants designed for her by Saint Laurent, when she married Thadée Klossowski in 1977.

Algerian born Saint Laurent had a long history of being inspired by the Orient, and in Jacob’s hands those influences have been updated and twisted to resonate with a woman of today. That meant a longer, leaner silhouette, the layering of rich fabrics such as silks and brocades, and the return of accessories as an important final touch to completing outfits. “It was done with such attention to detail, and I loved how Tim Blanks (the fashion critic at style.com) described it as Lana Turner going on a trip to Bali,” said Abdulaziz when speaking of a collection that also captured the spirit (and color sense) of Saint Laurent’s legendary muse and collaborator, designer Lou Lou de la Falaise. A not so surprising choice since de la Falaise wore a turban and harem pants designed for her by Saint Laurent, when she married Thadée Klossowski in 1977.

John Frederick Lewis’ “Lilium Auratum,” 1871. A look from Jean Paul Gaultier’s Spring 1998 haute couture collection.

John Frederick Lewis’ “Lilium Auratum,” 1871. A look from Jean Paul Gaultier’s Spring 1998 haute couture collection.  Some of the most interesting interpretations of Oriental costume have come from designers known for a minimalist approach to dress. In this case, Jill Sander and Alberta Ferretti whittle down the caftan to its purist essence, Spring 1994.

Some of the most interesting interpretations of Oriental costume have come from designers known for a minimalist approach to dress. In this case, Jill Sander and Alberta Ferretti whittle down the caftan to its purist essence, Spring 1994. Yves Saint Laurent would also be inspired by the costumes of the Ballet Russe when he created a collection under the same name. Frequently referencing North Africa (and Marrakech in particular where he had a home), his Spring 1991 collection included colorful harem pants and fez’s inspired by Léon Bakst’s costumes; For Spring 1992 he designed a Moroccan inspired ensemble. Saint Laurent also created Oriental inspired designs for his close friends; In 1977 he designed two wedding outfits for his muse Lou Lou de la Falaise; Bianca Jagger in an oriental inspired outfit at New York’s El Morocco, 1975.

Yves Saint Laurent would also be inspired by the costumes of the Ballet Russe when he created a collection under the same name. Frequently referencing North Africa (and Marrakech in particular where he had a home), his Spring 1991 collection included colorful harem pants and fez’s inspired by Léon Bakst’s costumes; For Spring 1992 he designed a Moroccan inspired ensemble. Saint Laurent also created Oriental inspired designs for his close friends; In 1977 he designed two wedding outfits for his muse Lou Lou de la Falaise; Bianca Jagger in an oriental inspired outfit at New York’s El Morocco, 1975.  For Fall 1994 London-based Turkish designer Rifat Ozbek showed one of his most influential collections in Paris (his first year showing there after presenting in Milan for several seasons). That year Ozbek was inspired by his Turkish roots and referenced Ottoman costumes. But take all those pieces apart and you had thoroughly modern clothes that were beautifully tailored, which was a hallmark of Ozbek.

For Fall 1994 London-based Turkish designer Rifat Ozbek showed one of his most influential collections in Paris (his first year showing there after presenting in Milan for several seasons). That year Ozbek was inspired by his Turkish roots and referenced Ottoman costumes. But take all those pieces apart and you had thoroughly modern clothes that were beautifully tailored, which was a hallmark of Ozbek.For the show he commissioned Phillip Tracey to design towering Fez’s based on those worn by twirling dervishes. Some came with ostrich feathers perched at their peaks, while others had floor skimming veils edged in silver coins. For the show, the models feet were painted gold and they walked on a runway covered in oriental carpets and rose petals.

The two outfits, worn by models Naomi Campbell and Yasmin Ghauri, demonstrate Ozbek’s talent at reinterpreting ethnic influences. In this case he took the traditional Ottoman military frock coat and reworked it into satin bustiers trimmed in grey fur, which were worn with ball skirts, mimicing the effect of harem pants when the models walked down the runway.

© THE POLYGLOT (all rights reserved) CHICAGO-PARIS

Tuesday, February 1, 2011

A Fashion Moment: Yves’ First Muse

In 1962, the French designer staged his first haute couture show and asked Victoire to be his star model. For that particular spring couture collection, Saint Laurent cloaked her in a chiffon veil, and sent her out in a lace trimmed gown that was an instant sensation. Her career as Saint Laurent’s muse was short lived however. Not long after the show, she gave up modeling to marry and start a family.

© THE POLYGLOT (all rights reserved) CHICAGO-PARIS